This year, I took the opportunity to participate in the 7DRL 2020 Rogue-like Jam. You can play my final entry here, and i’d love to hear any feedback, or answer any questions about it. What follows is a brief overview of the process I went through.

I’m a big fan of Rogue-like games, although I don’t mean in the strict Berlin interpretation sense. Games which have some form of procedurally generated challenge are at their root designed to be replayable. Well designed ones have a functionally infinite amount of content for you to digest. Rogue-likes expect you to repeatedly replay them over and over. So diving into creating my own, even in such a limited timeframe and scope, was alluring as a way to align my thinking more with the genre.

Hexception

I started with one simple idea; I wanted to be hexagonal. Hex-based grids have some neat traits, often exploited by tabletop games. They still allow the building of square rooms, creating man-made structures, but these can be at 60° angles, creating a more organic overall layout. It also presents 3 unique challenges across different disciplines. From a technical standpoint, I need to represent this hex-grid in a 2-dimensional space, which adds complexity to a lot of functions that would be more trivial on a traditional grid. There’s a design challenge in line of sight, which is a key feature of rogue-like games. Finally there’s an artistic challenge to the tiles themselves; by not having fully filled tiles we can create the aforementioned straight walls through our space.

Before a single line of code was written, I was trying to solve the latter two using the well known game dev tool of Google Slides. I jest, but Google Slides is fantastic for laying things out, and using it as a paper prototype proxy saves on a lot of screwing things up and starting over because moving, deleting and recolouring things is trivial. Line of sight was the first big challenge. Square grids certainly aren’t trivial, but hexagonal ones have an innate property that makes even the simplest case require a design decision.

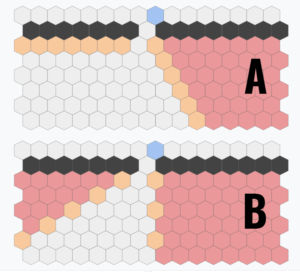

Shown above are two potential options I used early on to canvas opinion on what felt correct. Here, A and B show one of the simplest and yet most important things to decide in line of sight on a hexagonal grid. For the hexagon perfectly centred just below the player, one half is obscured, and the other not. I decided that by definition, this is a partially obscured position. Whilst this distinction never manifests in the game mechanics, it could have, and it ends up being very important in how I calculated visibility.

The A shows one interpretation of how obscuring could work, with every tile directly behind the blocked tiles being red, and the neighbouring edges being considered partially visible. Whilst this gives a generous view to the player, it seems to provide an absurd amount of vision on the left side. Conversely, option B is more restrictive in the view it offers, but people found it a far more intuitive representation.

In both cases, the map is being generated by applying algorithmic logic in flood-filling the spaces. Working from around the player in rings, each hexagon is evaluated based on it’s parents. For those on the 6 cardinal directions; they have only one parent and the logic is very simple. For the ones with two parents, each potential pair evaluates to a visibility. For example; having one parent which is a wall and one which is free space results in the child being a partially visible tile. The only difference between A and B is which visibility is dominant in the Partially Visible x Obscured pairing. I tried other techniques such as drawing lines between corners, a solution common to tabletop games. However, this felt unwieldy when being used to calculate many tiles, and yielded results identical to the above techniques (depending on the rules used).

After trials with many more layouts; neither satisfactorily solved for all cases, especially at long range. Two tweaks to ruleset A actually ended up being necessary to produce a decent result. Firstly, a child tile with parents that were Visible and Partially Visible would be Partially Visible. In more complex scenarios, this kept tiles as questionable, which felt more authentic at longer ranges. If the combat had ended up being ranged, i’m sure I would’ve imposed a penalty for firing into these zones. The second tweak was the one that stopped ruleset A from opening up too wide though. There is a second set of diagonals exactly in-between the six cardinal directions. For these additional 6 directions, you can draw a direct line back to the centre on every other ring of hexagons. For these special lines, there was the simple additional rule that the tile directly on a path back to the centre would also be included in the evaluation, and would take dominance in reducing the visibility. With this, we end up with the evaluation below, a mix of A and B. At long ranges with complex obstacles, this can still produce some less than intuitive results, but acts as a solid solution for the vast majority of cases within the players expected vision range (<10).

Artistically; I had also determined the tileset needed. A mere 8 tiles, shown above, that would be rotated and flipped, would cover all 64 possible edge cases (pun intended). By setting up the tiles as such and leaving some negative space, it would allow for the desired square rooms. A lot of the inspiration for this came from inspecting the room tiles for Gloomhaven, a boardgame that uses jigsaw like room pieces on a hexagonal grid to create a variety of dungeons. In the end, only a few small changes were made to this set. The small corner covering just two sides was replaced with a more symmetrical design. Whilst the corner did a fantastic job of connecting straight walls, working out the correct orientation was complex, and it didn’t support a lot of other cases. In the end, the simpler solution was better for this jam. Were the project to continue, I would retain the corner as an alternate to be used when appropriate. The half-and-half tile had a hexagonal pillar added to the middle to better convey that it was blocking line of sight. Finally, a Y-shaped piece connecting alternate sides was created. Whilst the T-shaped piece was adequate for these scenarios, it looked better to have all the options covered.

Finally, it was time to put semi-colons down in files and produce some code. In this case, a foolish mistake early on required me to rewrite a lot of what I had created. I initially created the map essentially as an offset square grid, as if every other row had shifted half a square to the right. This is a fine representation, but travelling on two of the diagonals is now difficult. Instead, I changed to treating it as a skewed square grid and having “up” be the North-East direction, two of the directions (E-W and NE-SW) are along the cardinal axes, leaving just one janky diagonal (NW-SE). There’s also a key choice in here of whether to have hexagons run vertically or horizontally, in the end this was largely aesthetic, I felt like as we naturally scan left-to-right the game read better in this orientation.

This work combined brought the first milestone, being able to navigate and edit a basic dungeon map, and ensuring the implementation of the walls and line of sight worked as designed.

Hacking It Together

By this point, I had also settled into an aesthetic. The crisp UI I had made leant to a nice glow, which in turn made me nostalgic for the CRTs of old. By adding some scanlines; the terminal punk style of the game had it’s foundation. I additionally added a diegetic game log. This had multiple purposes; building upon the aesthetic, providing player feedback for actions, but more importantly at this point it was a good debug feed to ensure that things were happening as expected.

However, I was also at the point of having to decide upon a core interaction mechanic for the game. After spending so much time looking at the dungeon layouts for Gloomhaven, I was remembering my fondness for it’s deck mechanic. As you traverse the dungeon you use cards, discarding them. Eventually, as you run out of cards and options, you opt to take a rest to retrieve cards back in to hand, but one is lost forever. This elegant system eventually drains heroes of their ability to do anything, but also thins their deck as they go, leaving only the strongest and best cards.

My original thought was to have the long rests occur between floors of the dungeon, and like Gloomhaven for movement to also come from cards. This would require very precise balancing though, as the levels would have to be carefully constructed to ensure the players had the resources to solve them. In the end, I kept movement as a free action, and only had the players have a deck of actions for defeating enemies. Similarly, I put the long rest in the player’s control, allowing them to do it at will as a free action (enemies do not get to move). Finally, as the game didn’t yet have a concept of HP for the player, making the enemies deal damage as removing cards meant there was only one stamina/health bar to keep track of for players, simplifying the fail state.

The actions themselves and the enemies are all highly data-driven. Each enemy is a prefab variant with different HP, damage, and speed. The actions are defined by a JSON, which specifies what pattern of tiles get hit, and how much damage is dealt to each tile. This made it easy to create a few variants early on, and later the Servers and Datahavens were implemented just as enemies with 0 movement and more HP.

Taking a moment to talk about the dungeon generation, with the challenges of the hex-based grid, and an innovative deck mechanic, I didn’t want to take on an elaborate map generation as well. I knew that other entire in #7DRL would likely excel at this, and that much prior work has been done that would mean this was not an area where my entry could shine. The simplest functional implementation was to generate dungeons based off perlin noise, creating mostly empty space (as well as carving out a space at the entry point to each level). To then populate the level with the enemies, exit, servers and titular data havens, I simply spawned them all at the same position as the player and sent them on a long random walk. This ensured that the key objects were always reachable, and connected to the player, although it is technically possible for the levels to only be 7 tiles in size and somewhat claustrophobic. In practice, the level generator creates reasonable levels to explore 99% of the time, which is great economy for a half dozen lines of code.

As the 5th Day drew to a close; I had a playable game with a complete loop, and started sending it out to friends for feedback.

Final Touches

One thing I’ve taken from all the Game Jams i’ve done is that most people finish too late. This is somewhat inevitable, things take longer than expected, and there’s a rush to get everything done you wanted. I always try to take on things that have extensible scope. My original thought here was simple : I want to make a hex-based roguelike. I knew that was achievable, and could front-load a lot of the thinking required to make it happen without even touching any C#.

Once I hit that first milestone; I re-evaluated the scope of what was left, and made decisions about what I did and did not want to focus on, but I had a goal of having a complete, theoretically shippable product by Friday, leaving the last third of the jam for two things. Presentation, and Polish.

I got that complete build to friends, and whilst I was waiting for feedback, I focused on my itch.io page. Getting it looking the part, having decent screenshots, and making sure the description was clear and explained both the intent, as well as acting as a guide to playing. In doing Game Jams in a professional setting, one additional piece absent here is often an accompanying presentation explaining what you did, and what you learned. Too often I have seen people forgo neatly wrapping up what they have made in favour of cramming in one more feature at the last minute.

With feedback from friends received, I was able to build out a list of Must Haves, Should Haves, and Could Haves, and roughly estimate how big of a job they were. In the end, most of the fixes were making the UI do more heavy lifting to Show the player how things worked, which saved on me having to Tell in the game description. I also did some more aesthetic polish, sanding off some of the rough edges that were present.

In retrospect, one of the things I should’ve done in this time is expand the number of programs in the game. As a data driven component, this was very easy to expand without compromising build stability. I was initially hesitant to build a massive variety of programs or enemies because the player would have to learn what they did by experimentation. As I expected playtime to be low, relying on this too much would just make it confusing. However, one of the additions had been visualising the attack pattern of the programs as you hover it over the grid. This meant that players no longer had to learn what all the programs did by experimentation, and I could’ve put in a lot more variety for low effort.

Submission Complete

The #7DRL was a relaxed jam to participate in, whilst exploring building something complete in a short space of time. I’d like to recognize @Cephalofair, designer of Gloomhaven, and @smestorp, creator of 868-Hack, from which I drew a lot of inspiration for the work here.

If anyone has any further questions about things I did, or didn’t do, or the decisions behind why I did or didn’t do things, then please tweet at me @dynamicsporadic. Also if you actually play Datahaven let me know what you think, and what special programs or enemies should it have added.